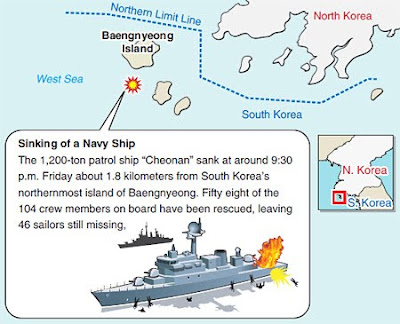

Like almost everybody else on the Korean Peninsula, I don't really know what to make of the explosion that sank the

Chonan-ham [천안함, aka the

Cheonan-ham]. It all sounds quite fishy, with the reasons given that it wasn't likely the doing of North Korea (shooting at a Flock of Seagulls — nobody hates 1970s pop

that much) sounding as iffy as if they had concluded just as fast that it

must have been North Korea. My stance right now is something akin to Joshua's at One Free Korea:

Personally, I do not find these statements to be persuasive. If this was indeed an attack, it’s unlikely to have been the result of an attack by a conventional warship, given that the North Korean Navy has no doubt learned that its conventional surface navy is no match for the ROK Navy.

On the other hand, the loss of the U.S.S. Cole taught us that even the most advanced warships are vulnerable to unconventional attack.

True that. And Joshua shows us a picture of a semi-submarine, one of several possible culprits.

But one has to wonder what motivations there are for the different scenarios being mentioned, which generally fall into two overriding categories of North Korean malfeasance or South Korean malpractice. As bloggers and commenters have noted, North Korea

does have the military capability to have sunk this ship stealthily (see above), as well as the prior bad acts to indicate a propensity, while South Korea's navy — well,

any navy — has a hundred different situations at their disposal that could have gone wrong, from improper storage of munitions to activating their own underwater mine.

Indeed, since this could go either way, the South Korean government and military are (mostly) being wisely prudent about figuring this out before either retaliating against the DPRK regime or letting them quite literally get away with murder.

While Seoul is looking at this cautiously, however, I am starting to find it more and more plausible that the North was actually behind this, either through direct attack or through a mine of theirs that accidentally or deliberately ended up on the ROK's side of the disputed Northern Limit Line which forms the de facto maritime border.

But the question remains: If deliberate, why would they do such a thing? Surely, they must know that if it were discovered that the North sank this ship, there would be retaliation, right? And therein lies the answer: there would be retaliation, but unless this became a far more frequent occurrence, there would be no all-out war (which, after massive devastation and death on both sides, would eventually mean the end of the Pyongyang regime). Simply put, South Korea is not going to invade the North and risk triggering artillery raining down on Seoul and its suburbs over the sinking of a single ship.

More importantly, however, retaliation would be

good for Kim Jong-il's government, whipping up the disgruntled masses against a common enemy at a time when people are still reeling from

the Great Currency Obliteration of 2009. Indeed, a retaliatory attack by ROK forces on any DPRK target at sea or on land — especially if North Korean soldiers or sailors came home in body bags — would prove a point of rallying around the regime as it reminds North Koreans of their

real enemy.

Calls to patriots that they defend the Fatherland would drown out the sound of a million grumbling stomachs.

Joshua points out other justifications:

Finally, all of this comes in the context of North Korea’s increased threats against the South in recent days, weeks, and months. The North has frequently provoked fights in the Yellow Sea to get the attention of South Korean presidents. As the North’s rhetoric has reached hysterical heights, South Koreans have learned to mostly ignore them. Maybe the North realized that it needed to regain some credibility.

The North Korean Navy certainly had other motives; chiefly, its likely desire for revenge after the beating it took in the last battle in November 2009, when a North Korean patrol boat got itself hosed down with a 20mm gatling gun. We saw this pattern with the sinking of the Chamsuri 357, which came three years after the ROK Navy sank one North Korean warship and severely damaged several others in another battle. The latter incident closely followed the aforementioned sinking of the semi-submersible off Yosu in December 1998. (All three incidents happened during my own tour in Korea.) For North Korean military officers, unavenged defeats are more than a loss of face. They can be grounds for a purge.

And if evidenced pointed to North Korean culpability, what would the ROK military do anyway? Attack a North Korean ship days or weeks after the fact? That makes them look like aggressors. Launch an aerial attack on a land target? That risks all-out war, but even if they do it, they again look like aggressors. But either way, the North wins if their goal is simply to coalesce the people's loyalty around the government.

This is a bit of an aside, and I admit it's flimsy evidence, but I also think it's telling that North Korea's KCNA propaganda machine has not released any message of condolence in Korean or English on its website, something that would be plausible (though not necessarily a given) if North Korea felt this truly were an accident on the part of South Koreans. After all, it's the kind of positive face that makes for good propaganda for winning over

chinboistas and fence-sitters: it makes Pyongyang look considerate and humane while also planting doubt in the public mind about their involvement.

Ultimately, though, it's best if Seoul takes this slowly and carefully. Check to see which way the blast went. If it came from within, be honest with the public about that and figure out what went wrong (the previous administration would make a nice scapegoat, so Lee's administration has no reason to shy away from this potential embarrassment). If it came from without, take a hard look at the possibility that a ROK mine was the culprit.

But if it ultimately turns out that the North is to blame, take action and mean it. Bomb the base from which the DPRK seacraft was sent, cut off all economic activities in Kaesŏng, Kŭmgangsan, or wherever: Do something real, relevant, and make it stick.

That is, if the North was behind it. Frankly, I have to admit that in the end that I'm not so sure. I trust my experience-informed gut, but unlike other situations involving the North, my gut doesn't really speak strongly here. This might really be nothing at all to do with Pyongyang, even though I just made the case that it

could be. The only thing I really want to make the case for is that Seoul had better get this one right.

Sphere: Related Content