It may not look like much, but it was quite spacious inside. Enough for two or three people to live and also have an office where two or three more could come in and work. I had three small dogs that ran around the modest yard in front and on the side, plus two cats living inside. (They were quite clever, having learned how to work doorknobs and escape from rooms in which mŏn-halmŏni tried to confine them.)

Off to the left you can see my

pimped-out minivan, parked on the narrow street that was designed decades even before the Korean War, when no one ever imagined Seoul would be home to millions of cars. It was one-way only, though no one could decide which way was the one way. At night people parked their cars flush with the wall, forcing motorists to squeeze by each and every car. Although it was a through street, it was not a heavily trafficked one, used only by people who lived there and already knew the score.

As best as we could discern, the house was constructed around 1935. The owner had lived there since it was first built, but when her husband died the memories became too painful and she moved to an apartment in southern Seoul and offered her home as a chŏnsé house (often spelled chonsei or jeonse; a refundable large-amount lease).

It was well kept for a sixty-year-old Seoul home built in a modern style when the tenants prior to me moved in, but they modernized the incoming water pipes and converted the heating system from yŏnt'an coal-burning to gas lines. The new tenant fixed up old colonial-era homes and flipped them or turned them into restaurants (he is running one now, near where the new US embassy will be).

His restauranting may have gotten him noticed by the local gangsters; I remember one scary night when I was about to go out and four large men with crew cuts, blazers, and faux turtlenecks were waiting at the front door asking for him. When I told them — without opening up the front gate — that he didn't live there anymore, they kept telling me to just call him down, and they wouldn't leave. It scared the sh¡t out of Halmŏni and probably wasn't good for her ninety-year-old heart. The men eventually left, though I think I'm not sure what eventually convinced them I was telling the truth. Just in case they were coming back, we called the police and asked them to make regular passes, which they did. (I'll tell you: it pays to know the police in your neighborhood before you ever need them.)

I lived there for several years, but the owner's daughter had dollar signs in her eyes and she forced her mother to sell. She knew her mother placed sentimental value on the building, so she promised to sell only to someone who would keep the building intact. We were forced to move (though our "eviction" was in line with housing law and leases) and I bought my own apartment using the same W80 million chŏnsé as a down payment.

(The rest was lent to me by Shinhan Bank. Though I'm not a ROK citizen, the apartment is in my name and my name alone, while the bank loan is in my name alone with no guarantors; I've had people who are so married to the meme that foreign citizens cannot own property in Korea that they simply don't believe me when I tell them — I'm either lying to them or I myself am the victim of a big scam involving the tax office, the local Ward Office, my real estate agent, and the bank. Anyway, if you're interested in buying property and would like to ask questions, I can let you know how mine went and maybe offer some advice.)

The house is no longer standing. The owner's daughter deceived her mother about what the new owners were going to do. They knocked it down and built a four-story cookie-cutter yŏllip chutaek (연립주택), those nondescript buildings with a different unit on each floor. It's not that bad-looking, but if you know what was there, it's sad.

The neighborhood itself, in northern Yongsan-gu, still has lots of old buildings like this scattered throughout, many of them in quite good condition because the owners were well off enough to build homes large enough that they continued to be good placed to live for decades to come. It also helped that they had the means to fix things up.

But this neighborhood itself may not be there much longer. In the last couple years it was rezoned for mid-rise housing: all homes ancient or recent are to be razed so that brand-spanking new apartments can go up in their place. This is not a shantytown like the neighborhood of southern Yongsan-gu where the recent violence took place; most of the people whose homes will disappear are either owners (who will get one of the new places) or tenants with means to move elsewhere. The people in my apartment complex are excited about the prospect of getting newer and larger places, though the economic downturn has put a damper on all that.

By the way, the property in front of which I was standing when I took this picture (in 2001) is a vacant lot. The house that was there was also one of these old colonial-era buildings. The tenants, two Americans, accidentally burned it down when they tried to incinerate their garbage so they could avoid buying the plastic bags legally required to discard one's trash.

The neighbors were furious and demanded their immediate arrest. The prosecutor demanded harsh sentences of five years each for the crime of arson. All across the city of Seoul, notices were placed in poorly worded English not to burn your garbage because you could burn your owner's house down.

Ah, I'm just kidding. The neighbors felt terrible for these two gentlemen, who were both nice guys who tried to speak Korean and be neighborly, even if they were irresponsible with fire. There were offers to let them sleep temporarily in neighbors' homes, and over the next few days, neighbors tried to help them find a new place to move into.

Sphere: Related Content

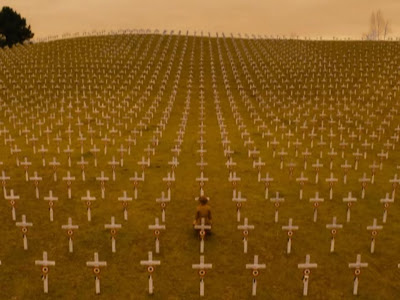

If I ever were to start having a caption contest feature on this blog, I think I'd start with this March 9 news photo.

If I ever were to start having a caption contest feature on this blog, I think I'd start with this March 9 news photo.

.jpg) Indeed it seems that Taiwan's

Indeed it seems that Taiwan's